How to Get Comfortable with being Wrong: The Mental Models that improve investing

Lets get inside your head to improve your investing & in doing so, prove the value of AI as part of your process

When I started my investing career I was eager to prove to my CIO that I was right, all the time. That’s how I believed you advanced in the industry - be right more than others. If not, then why would the CIO listen to you?

However, by the time I was running my own hedge fund, my perspective had changed dramatically. I told my analysts, “You have the license to be wrong. I’d prefer 10 ideas where 5 are wrong from you, rather than 1 idea which is right”.

What changed over those intervening decades?

Quite simply, it was the realization that being early and risking being wrong, was a more powerful skew to the expected payoff than being late and right. This is the investor’s paradox:

That to make large returns you have to be early and position ahead of the world changing. However, do that regularly and you guarantee that you will be wrong - often.

The Internal Conflict every Investor Faces

That however creates an internal conflict in most people. They’ve been taught from their first day of school to focus on learning facts not conjecture and aim for the highest percentage in every test. In other word’s we are conditioned from our earliest memories to “avoid being wrong”.

We award prizes to those who get the most questions correct in tests, and we give a big red “F” to those who get a lot wrong, warn them about their future prospects and haul their parents in for interviews. This conditioning, however fundamental to basic learning, is a problem when it comes to the discipline of investing.

The problem is that it attaches our identity to “being right” from our early years. But as we’ve already observed, the largest payoffs in investing are from being early, where being wrong is highly likely. When this occurs, we feel pain, anxiety and self doubt. Long periods of the market moving against you mean more of these negative emotions which can result in poor decisions when you reach your personal threshold. I have experienced this many times.

A Personal Experience

In May 2019, I championed an investment for my fund into Life360, the family safety and location-sharing app. I saw the company as differentiated and highly useful. I checked around and found all my parent friends were already using the app - it solved a real anxiety every parent holds. It quickly became a daily use app for myself and my wife with active kids running around managing their own lives while we worked. For that reason I felt it had some viral aspects. In fact, I was excited to a degree I rarely have been in my career about a stock. However, due to a poorly constructed IPO, loose register and ultimately the COVID pandemic, all we experienced was the stock falling.

We reached our pain point with the stock down 30%-40% from the IPO price and no sign of a reason this selling would stop. Exiting was a good decision in a bad situation as ultimately Life360 fell nearly 70% from its IPO debut over that chaotic period. However, the business wasn’t bad, the shareholder register was (which should have been properly cleaned up in the IPO), the stock was illiquid and market conditions exacerbated that. Having felt that I was simply wrong and full of doubt, I did not maintain a focus on the stock when I should have recognized that I was simply too early and missed that one aspect about the loose register in my due diligence. What transpired was the company delivering on its previously stated plan and ultimately rallying over 37x over the next 5 years from the trough! Adopting the mental model espoused in this post would likely have facilitated a re-entry to the stock down low and made this one of the premier successes of my career. However, I succumbed to fear of being wrong again and the investors’ paradox.

How do we adopt a better mental model to bridge the world we grew up in, to the world of the successful investor?

The world’s greatest investors provide the clue.

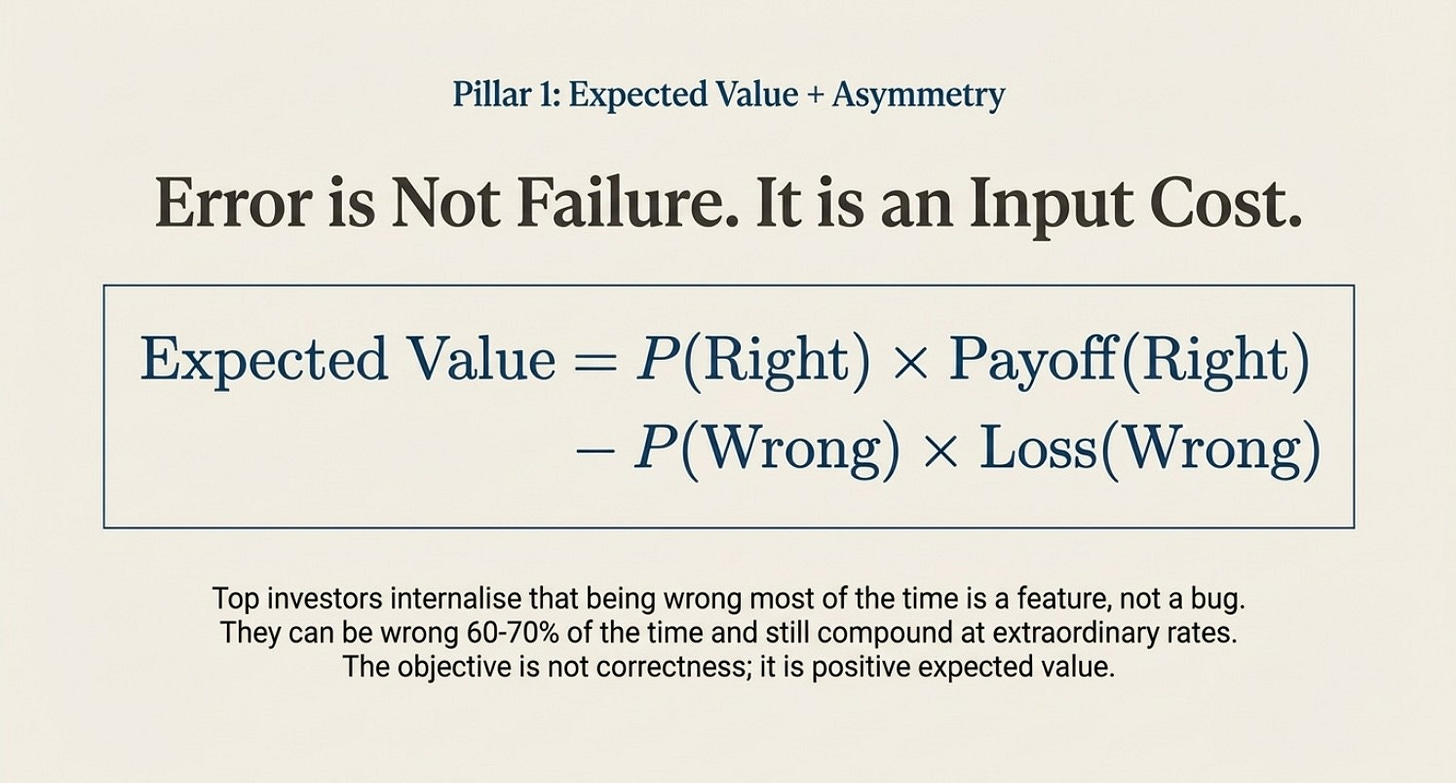

Accepting that getting things wrong is not a sign of failure but simply an input cost into being early and extracting large gains from your best investments, is the mindset change that the best investors use to underpin their strategies. They look at the world not in absolutes (“I am right”) but in a constant, iterative process of assessing the probabilistic, payoff weighted expectation in a world of radical uncertainty.

It is not feasible to be right all the time in forward-looking markets when the unknowns will always be greater than the knowns. So define the ultimate upside and assess the probability of this scenario. Then define the downside and choose investments where the expected value is the largest, not the single upside case. Buffett, Klarman and Benjamin Graham espoused the margin of safety principle - this is their way of skewing the expected payoff in their favor.

This concept is common across all the top investors. It reflects an implicit acceptance that being wrong is a cost of business with an investor’s job being to minimize the impact of losses and align the portfolio with asymmetric payoffs.

“Heads I win, tails I don’t lose much.”

— Warren Buffett

“It’s not whether you’re right or wrong, but how much you make when you’re right and how much you lose when you’re wrong.”

— George Soros

“The goal is to be right big and wrong small.”

— Paul Tudor Jones

“In venture capital, returns are driven by a small number of outliers.”

— Peter Thiel (Zero to One)

Investing is a Business like any other - Costs enable your Product

So how do investor’s shift their mindset from the concept of failure, to the acceptance of cost. In essence, they do not look at each individual idea and its success as a sign of their worth. Instead they focus on what they are doing as just like any other business. A CEO does not look at the cost lines in his or her business as failures. They are enablers. You must incur input costs, labor, selling commissions and even unexpected legal costs as a part of producing a finished product that is world class. You work diligently to minimize those costs to produce the highest earnings you can, but you will never remove them all.

It is no different in investing. Your investing is just another business like any other. Ideas that go against you are to be cut like an underperforming strategic project in a growth company - its not a failure, but an experiment that didn’t pan out. But you must have many experiments in order to keep evolving. Investors, like business leaders, keep learning from the things that go wrong (I learnt a lot from Life360) and they apply those learnings into all future experiments they back, to incrementally improve the success rate over time.

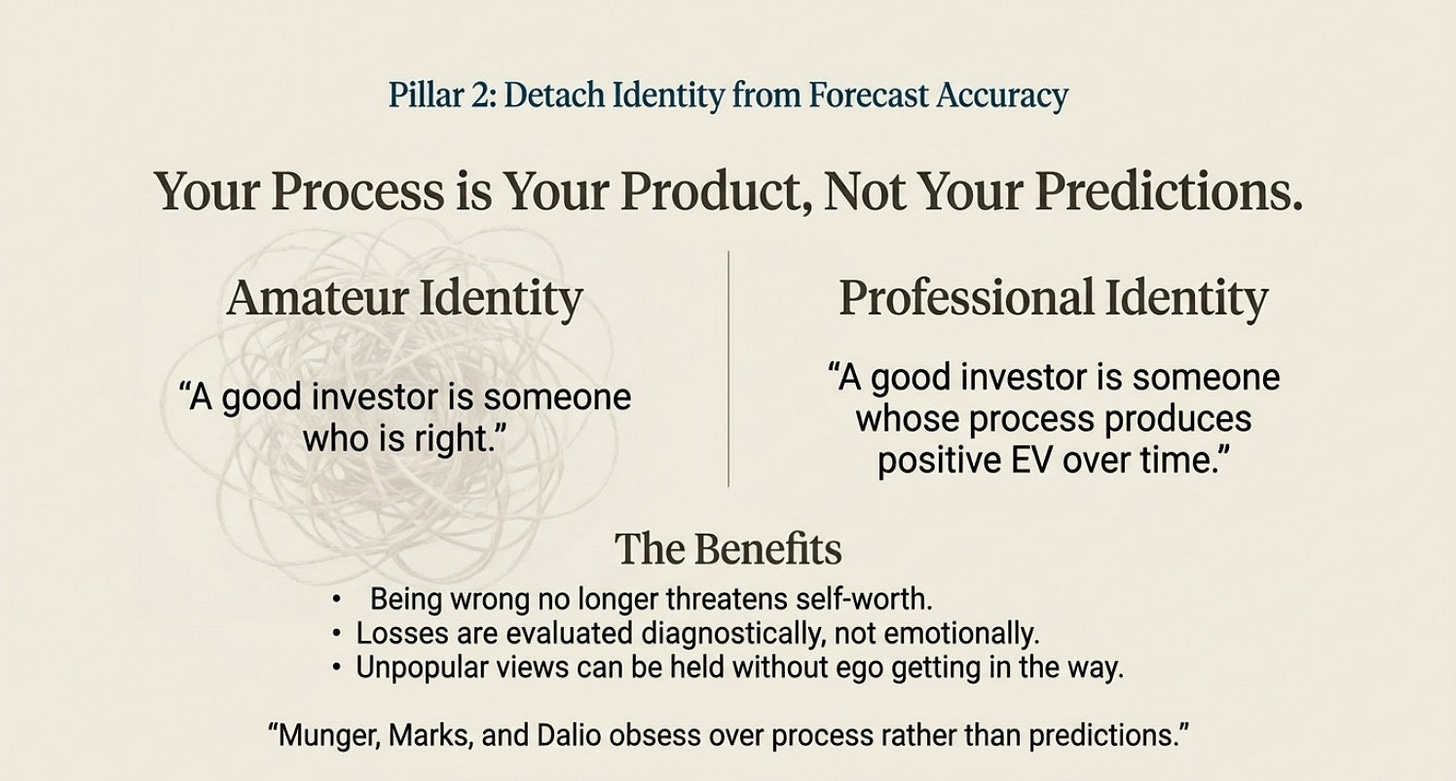

Process is Your Product

Again, sticking to the “investing is a business like any other” analogy, while your portfolio reflects a set of ideas at any point in time, it changes as the world changes. So don’t get too welded on to the individual ideas. Your portfolio is not your product - your process is. This is the underlying mindset shift that facilitates the move from dwelling on failure when things go wrong to “cut and move on”.

A portfolio is a fleeting expression of your process at any point in time, constrained by the radical uncertainty of the world and the conditions that exist. Once your portfolio changes - do you have a different product? No. The process remains the same. If it has produced good returns over time in the past, then it likely will again. Cutting poorly performing investments is not failure, but an act of strengthening your expected value which ensures your product remains true to its promise. Under this mindset, this is a positive act that should be just as rewarding as watching good investments perform.

Magnifying the Asymmetric Payoff

“When you have conviction, size matters.”

— Stanley Druckenmiller

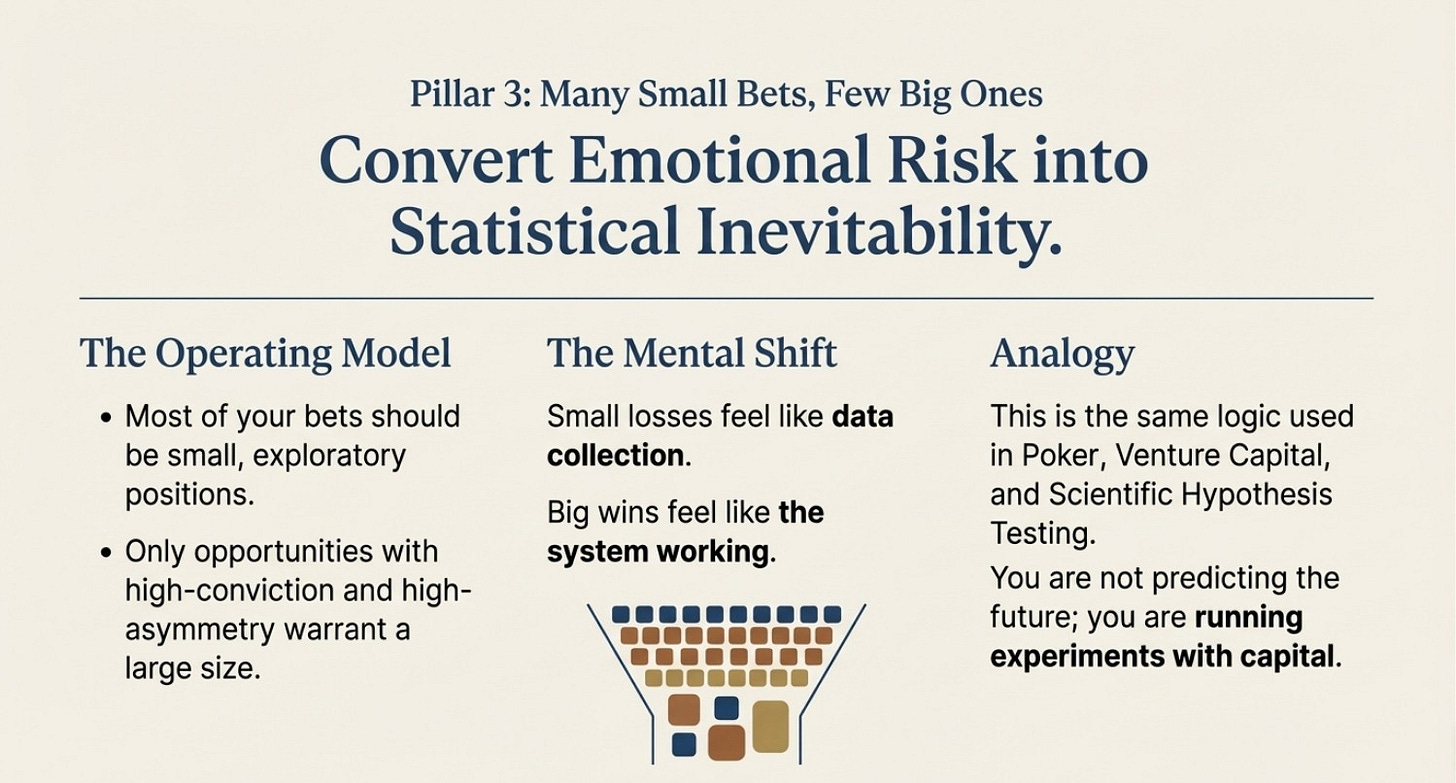

What Druckenmiller is referring to is that not all positions have the same payoff at any point in time. The equal weight portfolio is not expressing equal conviction, but an implicit recognition that the investor can’t distinguish between the payoffs of each position. At my hedge fund, we would start new positions (“experiments”) small, with a detailed thesis called C.I.V.C - Change, Implications, Valuation, Catalysts. Or in other words, whats changing (that will generate surprise), what are the implications on the value drivers (where is the market wrong), how does that change the valuation as the market catches up and what are the catalysts that will make that happen?

As we explicitly emphasized “change” in our process we were specifically targeting being early to capture the largest payoffs. The risk is therefore being wrong. We started positions at 1-2% of NAV but as a thesis played out and more data points were captured that proved the thesis on track, we could quickly scale to a position of 15%. Our portfolio would look at any time like a convex curve. Many small bets, a few large. The composition of those large bets would change as share prices moved and the information set changed. We dynamically aligned our big bets with the strongest payoffs that we saw.

This is what Druckenmiller espouses as well. Its results in a system where small losses can be seen as data collection, while big wins prove the system is working.

The Ultimate Mindset: A Portfolio of Experiments

In the field of science there is a reason a hypothesis is expressed as the “null” variant. The ultimate goal is to find enough evidence to reject the null, showing its unlikely to be true and thereby accepting the “alternate”. The null hypothesis is usually stated as there being no relationship between two variables (“the new drug has no effect on” or “the stock will not outperform the market”). This implies that scientists consider failure of a novel experiment as the status quo and look to prove this wrong by evidence.

This is the exact opposite to what most investors do. They assume they are on to the next big winner and state their total conviction. “This is a 10 bagger”! Its not an experiment to them - its a certainty. Yet they have a portfolio of 5% equal weight, “10 baggers”. Alternatively they have their largest positions in stocks that are already up 200%. This makes little sense. When market conditions change and many positions drop 50% or more in what are likely highly speculative investments, they simply reinforce the doom loop of failure. High expectations quashed.

When you shift your mindset to the “portfolio of experiments” concept, an investor is in reality recognizing there is a high risk of being wrong and accepting that as part of the job. However you have an initial set of data and theory that suggests the position has a good chance of working, otherwise you would not enter that experiment. Your job is to gather further evidence to build to a positive conclusion. Many top investors state that they assume they are wrong at the outset. That is, they accept the input cost of being wrong up front, so it is not a failure if that comes to pass. That has them on alert for all available incoming data to reassess the payoff. As more data supports the alternate hypothesis (“the drug does reduce the disease” or “the stock will outperform the market”), then the expected payoff builds and they take a large position.

This process better reflects the reality of both science and investing. You start with more unknowns than knowns in any new position. You may be familiar with the feeling that over time, you come to know a stock far better - what shifts it, who the investors are, what their expectations are etc. This is data gathering in action. To be early in a trade, you cannot find all this out upfront. That reinforces the nature of investments being just like experiments, and as such, the scientific method of considering the “null” upfront, helps investors make more rational decisions and size bets appropriately

All this is in aid of the overriding objective of maximizing the expected value of your portfolio (and your product - the process) at any time.

So How Does AI Change the Game (and help maintain a productive investor mindset)

AI helps shift an investor’s mindset by systematically separating process quality from outcome quality, something humans struggle to do under emotional stress or due to our fear of being wrong, which introduces bias. Through dispassionate reasoning and data gathering, AI reframes each investment as a structured, independent experiment rather than a single verdict on an investor’s own competence. My recent survey into Best Practice use of AI for Investment Research showed that many professional investors are using AI as their “red team” or “null hypothesis”. They load in their thesis and data and get the model to challenge it, then find evidence which either supports or rejects those challenges. From there they and the model can assign relatively unbiased probabilities to each scenario. In essence, AI strengthens their path to aligning with asymmetric payoffs.

AI also excels at synthesizing both the bull and the bear case on any stock. Considering the opposite point of view in detail is often difficult for a human. Our minds have been conditioned by too many years of “argue your point and don’t admit defeat”. Some of my most valuable interactions with AI on stocks are synthesizing both the bull and bear case, then uploading recent financial accounts, management discussion, presentations and transcripts and getting the model to dispassionately assess which case the evidence best aligns to. This is a continuous process as more data arrives and allows you to provide additional evidence to the model and see how it changes the perspective.

As importantly, AI can enable investors to internalize payoff-weighted thinking rather than accuracy-based thinking. By modelling upside, downside, and distributional outcomes across many ideas, AI makes visible what top investors intuitively understand: that a small number of asymmetric wins dominate long-term returns. This reduces anxiety around being wrong often, because the system continuously demonstrates that correctness frequency is far less important than sizing, convexity, and discipline. Over time, this conditions the investor to behave more like a portfolio manager than a forecaster, aligning mindset with the core traits of great investors: probabilistic reasoning, emotional detachment, continuous updating, and patience under uncertainty.

AI is the investors own “Dr Spock”. Coldly logical, rational and willing to challenge. That can only help investors over the long term.

As always

Inference never stops. Neither should you

Andy West

The Inferential Investor